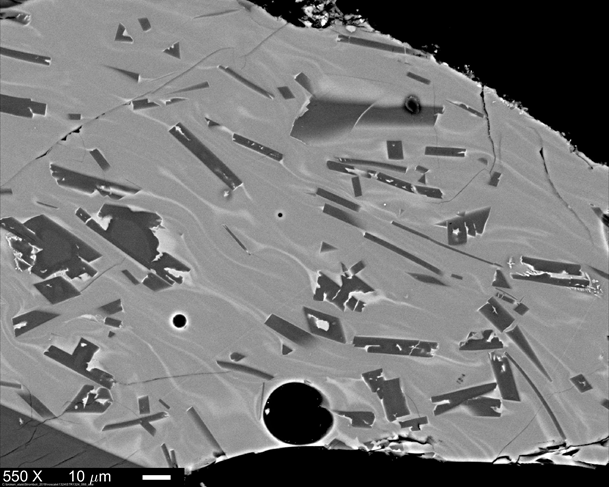

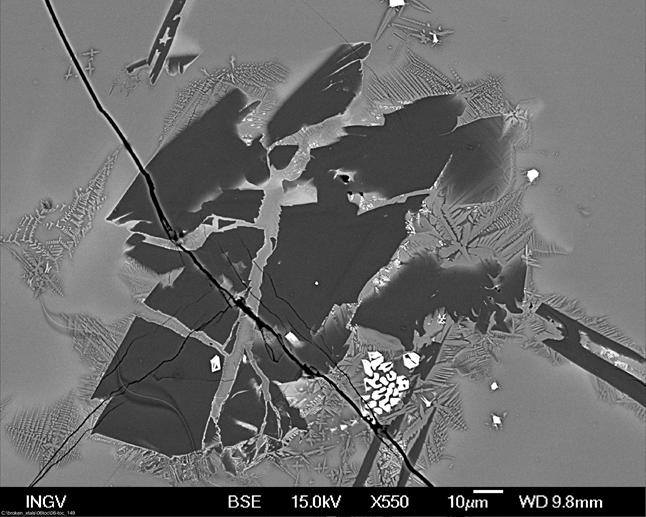

Immagine al microscopio elettronico di un frammento di cenere vulcanica. Il vetro vulcanico (lo sfondo grigio uniforme nella foto) è intatto, ma un cristallo fratturato (grigio più scuro) testimonia il processo di fratturazione e rimarginazione del magma nel corso dell'eruzione.

Scanning electron microscope image of a volcanic ash particle. Intact volcanic glass (grey uniform background) includes broken crystals (darker grey) that record the fracturing and healing of magma during eruptions.

Immagine al microscopio elettronico di un frammento di cenere vulcanica. Il vetro vulcanico (lo sfondo grigio uniforme nella foto) è intatto, ma un cristallo fratturato (grigio più scuro) testimonia il processo di fratturazione e rimarginazione del magma nel corso dell'eruzione.

Scanning electron microscope image of a volcanic ash particle. Intact volcanic glass (grey uniform background) includes broken crystals (darker grey) that record the fracturing and healing of magma during eruptions.

Eruzioni esplosive: ecco come si rompe il magma

Una nuova ricerca svela come si formano la cenere e lapilli eruttati dai vulcani con un magma particolarmente fluido come l’Etna e lo Stromboli

[Roma, 30 marzo 2021]

Benché particolarmente fluido, il magma basaltico di vulcani quali Etna e Stromboli si frammenta come un bicchiere di vetro che cade. Ma, proprio perché fluido, molte delle fratture si ricompongono, riducendo la quantità di cenere eruttata e il suo impatto su chi vive intorno ai vulcani.

Questa è la scoperta di un team di ricercatori dell’Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV), dell’Università di Monaco (Germania) e delle messicane Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas di Tuxtla, e Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México di Mexico City. Il lavoro Fracturing and healing of basaltic magmas during explosive volcanic eruptions è stato appena pubblicato su ‘Nature Geoscience’.

“Con questo studio”, spiega Jacopo Taddeucci, ricercatore dell’INGV e primo autore del lavoro, “abbiamo voluto comprendere le modalità di formazione delle particelle vulcaniche, dalle bombe vulcaniche, che possono raggiungere le dimensioni di una automobile e che cadono intorno al cratere, alla microscopica cenere vulcanica che, invece, si disperde anche a migliaia di chilometri. Tutte queste particelle si formano quando il magma che causa una eruzione si frammenta in modo esplosivo. Per i magmi basaltici, come quelli dell’Etna o dello Stromboli, questo processo non è ben compreso e ci sono teorie contrastanti tra i ricercatori”.

In ogni tipo di esplosione, dalle piccole esplosioni di Stromboli che attirano i turisti, ai pericolosi parossismi dello stesso vulcano, fino alle fontane di lava che in questi giorni stanno caratterizzando le attività dell’Etna, il magma basaltico mostra specifici comportamenti.

“Studiando i campioni di un numero consistente di eruzioni basaltiche”, prosegue il ricercatore, “abbiamo scoperto che in tutti i campioni sono presenti dei microscopici cristalli rotti. Per capire l’origine di questi cristalli abbiamo effettuato degli esperimenti di laboratorio dove abbiamo fuso delle bombe dell’Etna e, poi, abbiamo fatto esplodere la roccia fusa iniettando del gas a pressione. Quello che abbiamo verificato”, aggiunge Taddeucci, “è che i cristalli sono stati rotti dalla frammentazione del magma. Le caratteristiche di questi cristalli ci dicono che il magma basaltico, all’apparenza fluido, in realtà si è frammentato in maniera fragile, come un bicchiere di vetro che cade. Ma ancora più interessante è la scoperta che, siccome alla frammentazione il magma è ancora fuso, molte delle fratture che si sono formano ‘in rottura’ poi si risaldano. Questo processo di ‘ricomposizione’ delle fratture riduce la quantità di cenere eruttata dal vulcano”.

“I risultati ottenuti”, prosegue il ricercatore, “ci aiutano a stimare quante particelle si formeranno nelle future eruzioni e di che dimensioni saranno, punto essenziale per affrontare le conseguenze delle eruzioni esplosive. Inoltre, queste nuove conoscenze ci guidano anche nel percorso inverso, ossia nel ricostruire le dinamiche delle eruzioni del passato a partire dallo studio dalle particelle che hanno lasciato. È indubbio che questa scoperta apre nuovi orizzonti per lo studio del vulcanismo esplosivo” conclude Jacopo Taddeucci.

#ingv #vulcani #stromboli #etna #magma

LINK:

Explosive eruptions: this is how magma breaks down

New research reveals how ash and lapilli erupted by volcanoes with particularly fluid magma such as Etna and Stromboli are formed

[Rome, March 30, 2021]

Although particularly fluid, the basaltic magma of volcanoes such as Etna and Stromboli shatters like a falling drinking glass. But, precisely because it is fluid, many of the fractures are healed, reducing the amount of ash erupted and its impact on those who live around volcanoes.

This is the discovery of a team of researchers from the italian National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV), the University of Munich (Germany) and the Mexican Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas in Tuxtla, and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Mexico City. The work Fracturing and healing of basaltic magmas during explosive volcanic eruptions has just been published in 'Nature Geoscience'.

"With this study", explains Jacopo Taddeucci, researcher at INGV and first author of the study, "we wanted to understand the modalities of formation of volcanic particles, from volcanic bombs, which can reach the size of a car and which fall around the crater, to the microscopic volcanic ash which, on the other hand, is dispersed up to thousands of kilometers away. All of these particles form when the magma causing an eruption breaks up explosively.

For basaltic magmas, such as those of Etna or Stromboli, this process is not well understood and there are conflicting theories among researchers ".

In every type of explosion, from the small explosions of Stromboli that attract tourists, through the dangerous paroxysms of the same volcano, to the lava fountains that are characterizing the ongoing activity of Etna, basaltic magma shows specific behaviors.

“By studying the samples of a large number of basaltic eruptions”, the researcher continues, “we discovered that in all the samples there are microscopic broken crystals. To understand the origin of these crystals, we carried out laboratory experiments where we melted Etna bombs and then blew up the molten rock by injecting gas under pressure. What we have found”, adds Taddeucci, “is that the crystals have been broken by the fragmentation of magma. The characteristics of these crystals tell us that the basaltic magma, apparently fluid, has actually fragmented in a fragile way, like a falling drinking glass. But even more interesting is the discovery that, since the magma is still molten upon fragmentation, many of the fractures that are formed at fragmentation' later heal. This healing process of the fractures reduces the amount of ash erupted by the volcano".

“The results obtained”, continues the researcher, “help us to estimate how many particles will form in future eruptions and what size they will be, an essential point for dealing with the consequences of explosive eruptions. Furthermore, this new knowledge also guides us in the reverse path, that is to reconstruct the dynamics of past eruptions starting from the study of the particles they have left. There is no doubt that this discovery opens new horizons for the study of explosive volcanism "concludes Jacopo Taddeucci.

#ingv #volcano #stromboli #etna #magma

Link:

...